This article from Rachel Rabbit White, who blogs at a site bearing her own name, was picked up by AlterNet (or written for?) and given a much wider and much deserved readership. Somehow I missed this, I think, when it first was published.

Oh yeah, it's from 2011, and it was written partly in the aftermath of Rep. Anthony Weiner’s "dick-pic scandal." Around that time, the prevailing commentary online was that “wangs are ugly” or "look angry."

Rachel clears up a few things and she exposes how this "size matters" stuff hurts a lot of men.

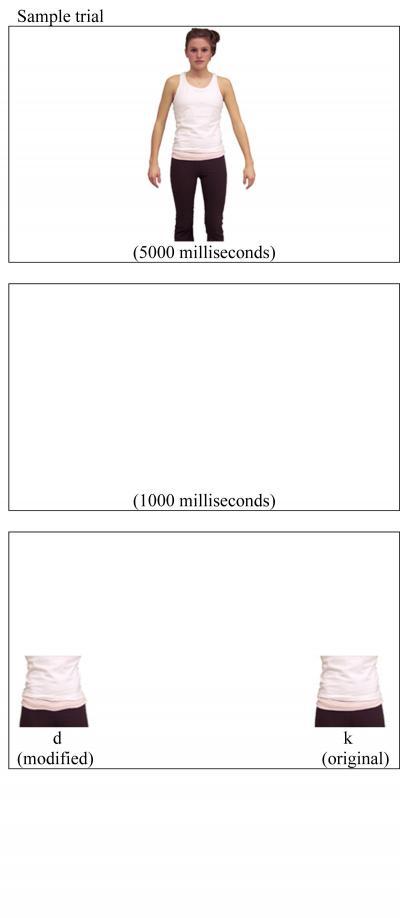

Read the whole article.June 22, 2011 | Rachel Rabbit WhiteIn 2008, New York Magazine reported on a small group of men sitting in a bleak room on 13th street, commiserating, offering support, and trying to come up with something other than “small penis” to describe their "affliction":"We’ve been throwing around other names,” says John Miller, a stocky man with a therapeutic manner. “People have suggested firecracker or sparkplug as words with positive connotations."While New York Magazine ostensibly covered this “Small Penis Support Group” as an esoteric joke, the sentiment behind the group isn’t so rare. A small penis support forum, Measuerection.com, boasts over 10,000 members. A user named “Nubdick” sums up the movement: “I’ve been ridiculed and made fun of by women so much that I've pretty much given up. It doesn't help that the media is constantly barraging us with 'Size DOES matter' -- from music to TV shows and movies, even advertising.”

Then there's a porn-world where every man is over 8 inches. In the phenomenon of monster-cock porn, in which guys (wearing realistic sheaths) give the illusion that a penis can rest on your heart. And let's not forget the e-mail spam that tells my vacant hotmail account, “Rachel, she knows you aren’t big enough.” Or the rigid male gender roles that prize stoicism, that discourage talk of emotions or inadequacies.

In small penis support groups, there are a number of men who aren’t actually small but just feel like they are. And time and time again on the forums, standard sized men say they are going under the knife for penis enlargement surgery--a practice that is described as “experimental at best” by the American Urology Association. A study by researchers at St. Peter’s Andrology Center and Institute of Urology in London followed 42 men undergoing this procedure. Researchers found that most of them had “normal” sized penises--and after the procedure, only 35 percent were satisfied with the results.

American culture sends a message about the penis that is confused, at best. In the wake of Rep. Anthony Weiner’s dick-pic scandal, the theme that “wangs are ugly” spattered the Internet, the media (wrongly) assuming that’s just how most women feel. The Washington Post even ran a sweeping op-ed in which writer Monica Hesse mused, all too predictably: “How about a picture of you, sweaty, cleaning out the storm drain? So sexy!” And before all this, the first big laugh in this summer’s blockbuster Bridesmaids comes from the two main characters joking that penises are ugly and look angry.

So it seems like in American mainstream culture, “wangs are ugly,” but unlike the Greeks who dealt with penis anxiety by preferring petite genitals, we want ours super-sized anyway. Last year, a “kiss and tell all” account of how Mike “the Situation” Sorrentino had a “small penis” was passed around the Internet with zeal. Penis shaming, it seems, is culturally acceptable. Our mash-up mantra seems to be: wangs are ugly but we, as the '90s club-hit chimes, “don’t want no short dick man."

What we know about the average penis size in America, adds up to--sorry--dick. The size statistics we’ve been relying on--those of Kinsey or a widely used Lifestyle survey--asked men to measure themselves and self report their size, which unsurprisingly seems to only leave room for flubbing upward in inches. There is also the question of where to measure from, and erect or non-erect? Stretching the penis? All this considered, the most widely reported stats confirm average penis size falling somewhere between 5-6 inches.

Along with the pressure to be “well endowed” is more policing of Western male beauty in general. The Calvin Klein ad staring down on men on the bus conveys the message that desirable men are hairless with perfectly formed abs, a great haircut, and a bulge in the pants. Not to mention he has to spend $40 on underwear.

SUNDAY, JULY 29, 2012

SUNDAY, JULY 29, 2012